Trigger warning: This article discusses sexual assault.

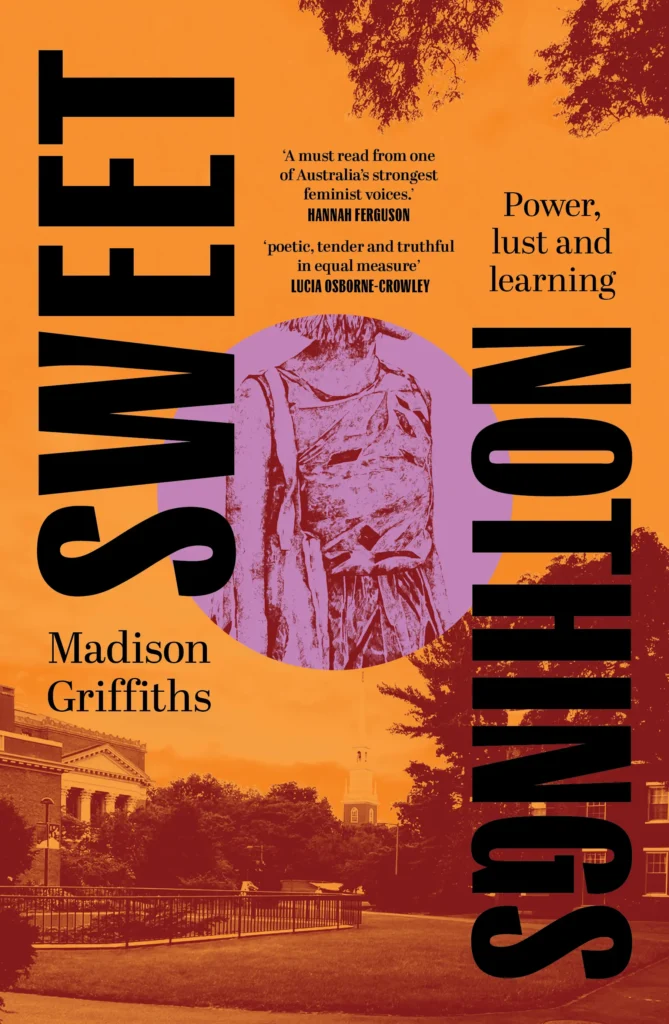

‘Consent’ is the single, seven-letter word that sits atop my investigation of student-professor romance, as if to haunt it. In the grand scheme of feminism, talk of consent has certainly earned its mantelpiece post. Anna Leszkiewicz for the New Statesman refers to “consent culture” as a “shorthand for an abstract ideal, an alternative to the rape culture that feminists widely agree dominates society today.” When setting out to write my book, Sweet Nothings, I knew that in deciding to focus mainly on ‘consensual’ student-teacher relationships as they occur in Australian universities, the seemingly affable embrace (or bandaid) of consent would—for some—make such relationships appear somewhat pasteurised. Because what’s worse than a professor who routinely sleeps with his students? A professor who assaults them.

Katherine Angel, author of Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again, acknowledges how consent culture is forced to cart around an impossible load. By that she means, it is seen as the endmost neutralising agent of bad, wrong, ill, wicked sex. If consent was always the remedy, why did I feel it a lousy bandaid when I reached for it while writing ‘Sweet Nothings’, insisting it make sense of my own predicament? Around a decade ago, I had eagerly engaged in a romantic relationship with one of my tutors at university. Now, well into his professorship, I have come to see myself as a member of a small, sad troupe: one of a few of his former-students-turned-lovers. This outcome I didn’t envisage when I met him at 19 years old, nor the sense of humiliation that followed.

I have had professors openly admit (both to me, and publicly) to having had many a dalliance with a younger, female student. Just recently, one wrote fondly about procuring a relationship with an 18-year-old student while he was her 36-year-old professor, in a close-reading of my book he published online. Consent, consent, consent, these men nag at length. He accused me of playing ‘fast and loose’ with power, to which I’d say: these men play fast and loose with academic integrity, and—of course—consent. A woman studying in order to progress her career ought not to be burdened by undue power equations in the realm of sex (and her ‘power’ is always, according to these men, limited to her beauty or her youth, and rarely much else).

Amia Srinivasan writes in The Right to Sex, that “any argument about consensual teacher-student sex misses something crucial if it doesn’t observe that these relationships typically involve male professors sleeping with female students”. When I started noticing how gendered these dynamics were, that they almost always involved older male teachers and younger female students, I considered them a sexist phenomenon. Not illegal, or non-consensual, or illicit. Sexist. Lazy.

I don’t care to take for granted that female students—those forced to contend with HECS debts, career instability and the sanctity of their own professional futures—must too navigate the heady wants of their male educators, who are regularly comforted by a six-figure salary, academic tenure and the cushiony embrace of ‘consent’. As Srinivasan reminds us, “the question isn’t whether genuine consent or real romantic love is possible between teachers and students. Rather, it is whether real teaching is possible”.

If a female student is to make sense of pleasure, power and sex politics entirely through the modus of consent, the burden of such is to fall squarely on her shoulders. She is to emphatically know what she wants, and what she doesn’t. Both now, and in a decade’s time. She is to definitely see herself as unshakeably whole. What sort of student would she be, then, if she were to arrive at the classroom fully-formed?

Just as we ought to interrogate whether real teaching is possible if teacher-student relationships are met with a shrug in academic institutions, we ought to consider whether a female student has the space to be just that under such conditions: a student. Challenged, provoked, inspired and shaped.

If this article raises any concerns for you, please call 1800RESPECT for around the clock counselling and support. Alternatively, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Also read: Madison Griffiths on International Women’s Day, exploring Our Bodies, and what’s next