Mumbai: It is the fifth month of pregnancy for Tara*. By now, the discomfort has gained a note of normalcy. Her skin grows warm like a bonfire and the body shivers in response, signalling the onset of a recurring fever. There’s dizziness, nausea, chills. Fatigue, more than anything. But these are things you get used to – the physical distress of bearing a child is as fabled as it is familiar.

But the familiarity morphed into fear earlier this year when the high temperature persisted. It wasn’t just 102 degrees three nights in a row, but a throbbing headache, nausea, and a sickly pallor that alarmed the couple. Tara’s husband rushed her to a nearby hospital in Chhattisgarh’s Raipur. The investigation revealed abnormalities: her white blood cell count was high, the platelet count had sunk like stone.

The two things she understood – fever and fatigue – were in fact signs of dengue. Recounting her experience, Radha Pradhan, a nurse trainer and social worker in Betul, tells me: “They [Tara and her husband] were surprised. It wasn’t until they reached the hospital, got all tests and investigations done, that they realised these are signs of dengue.”

Pregnancy comes with risk. But what happens when the risk is compounded by dengue, the world’s fastest growing vector-borne disease? Dengue fever is endemic to 128 countries, with the bite of the infected Aedes species (Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus, which is also responsible for transmitting Zika and Chikangunya) mosquito putting as many as 3.6 billion people – half of the world’s population – at peril of illness, and even death. But that the risk is more pronounced among tropical and sub-tropical countries like India, with some of the world’s poorest populations, makes it neglected in the global public health discourse. Dengue is thus classified as one of the 20 neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) – maladies that also function as “prox(ies) for poverty and disadvantage.”

A disease can’t be willed into submission, however. Dengue epidemics are increasing in frequency and magnitude. Once upon a time in India, dengue was limited to a handful of states like Delhi, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu; now 70-80% of Indian states have documented dengue cases. The union territory of Lakshadweep also succumbed to this trend when it reported its first dengue case this year. This is partly due to human mobility, urbanisation, and poor waste management – but global warming also plays a role in hastening dengue’s spread, according to experts. When mapped, the disease burden has increased 30 times over the last 50 years specially during the monsoon season.

Tara’s story, then, feels like a shuffling tide before a storm. A neglected tropical disease like dengue will worsen with the climate crisis, and disproportionately impact a demographic – women, and pregnant women in particular – that has restricted access to healthcare due to systemic, cultural, and economic barriers. “Malaria can be deadly in pregnancy. Covid-19 can be deadly in pregnancy. Similarly with dengue. These diseases eventually become a significant reason why pregnant women are dying,” Dr. Somya Gupta, a Delhi-based gynaecologist who has treated some cases, tells me.

Paucity of data

Some 1,000 kilometres away, in Jamshedpur’s Tata Main Hospital, Dr. Ruchita Sinha was zooming in on this turbulence. In 2017, there was a dengue outbreak in the area, 556 reported cases – some consumed by fever, others convulsing with dizziness and nausea. Many of these people were also pregnant. “How does dengue really impact pregnant patients? We are not very sure. And so we just had to look into it,” she tells me.

Dr. Sinha, along with two other practitioners, retrieved case records to examine the complications and maternal outcomes in people who are pregnant. Their study, published in the Journal of Family Medicine and Care earlier this year, found high risk of complications.

Essentially, every complication during pregnancy – preterm labour, postpartum haemorrhage (increased bleeding tendency), miscarriage – is no longer a possibility, but is spoken of in terms of a probability in the context of dengue. “There are chances they develop Dengue Shock Syndrome, or severe dengue, which can cause hemodynamic havoc, and multi-organ failure, and the patients usually die because of it,” Dr. Sinha adds. Of all patients, five had severe dengue with a mortality of 60% (dengue is classified into undifferentiated fever, dengue fever, and dengue haemorrhagic fever – with the haemorrhagic fever being the most severe form of the disease).

At one level, a pregnant woman goes through several physiological changes: food travels down the gut much slowly, the body needs more oxygen, things like that. These changes also make them likely targets of several viruses, increasing their likelihood of contracting diseases like dengue, chickenpox, influenza – even Covid-19.

Take the platelet count. Platelets are tiny cells responsible for clotting of blood, and with their reserves at a low, the blood refuses to clot and the person is more likely to bleed out. Pregnant women usually have a low platelet count due to something called gestational thrombocytopenia. This low reserve complicates their experience of dengue. “If the [pregnant person] also develops dengue, then platelet count could become critically low, and it would be a double whammy for them,” explains Dr. Gupta. Coupled with this is also a complication whereby the placenta – an organ that develops in the uterus to sustain the foetus with oxygen and food – detaches itself from the womb due to clot formations. This risk of abruption is increased during dengue.

Other studies are picking up on this precarity. Between July 2016 and June 2017, among the 256 pregnant people admitted to Chandigarh’s Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research – a centre for high-risk pregnancies — these were the case outcomes: 10 developed post-partum haemorrhage, eight developed acute kidney injury, seven required ventilatory support. Four had acute liver failure. 18 women had evidence of shock. The authors of the paper concluded: “Dengue in pregnancy adversely affects maternal and foetal outcomes with high maternal mortality of 15.9%. Prematurity and postpartum haemorrhage are significant risks to mother and baby.” This is similar to other tropical diseases like malaria: The risk of death after contracting malaria in pregnant women is 50%, as compared to a 15% risk profile in non-pregnant women.

A 2018 paper outlining experiences of women in Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam revealed a similar health risk. The problem, it reiterated, was that researchers still know very little about how dengue impacts the pregnant women or the foetus. Without this knowledge, how would one even begin thinking about treatment?

Dengue as a tropical disease is evolving too. “In the past dengue was predominantly a childhood illness. However, there has been a shift in the age of infection in many countries,” Dr. Neelika Malavige, a Sri Lanka-based researcher working with Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), and a doctor who has studied dengue’s spread, explains. The average median age of dengue infections is shifting forward, such that adults form the major caseload as opposed to children and adolescents earlier. Moreover, the awareness around how dengue spreads or how people can protect themselves has always been meagre. Cases are always scattered across states, and governments rally up health information campaigns only when the numbers go up. The effect of dengue is not like Covid-19. With Covid-19, the awareness was significant since it had a widespread effect on people. Dengue wanes in comparison.

The compounding effect of under-diagnosis and under-treatment makes dengue infection in pregnancy a high-risk state – complications and severe dengue is several times more likely to occur in pregnant women than non-pregnant women. “But I don’t think people are aware of this fact at all.”

The problem, as it is currently framed, is dengue is rapidly spreading, and is particularly affecting pregnant women. But pregnant women are rarely taught to see it that way.

Breeding bias

The literature about the effect of dengue on pregnant patients is very sparse. A gap in knowledge thus persists, which complicates how a disease is communicated about, its severity perceived, and treatment accessed. Radha laments, “Jo cheez hum dekh nahi rahe, sun nahi rahe, usko jaan ne mein hum interest nahi lete.” What we can’t see, what we refuse to hear, it is automatically deemed unworthy of our attention.

For instance, stagnating water is a breeding site for the Aedes aegypti. Gendered social norms mean women are responsible for household chores like washing clothes, utensils, and dishes. Their overall exposure to dirty water – a site of infection – is then much higher. A 2017 study examined the awareness and health-seeking behaviours among people living in New Delhi’s Jhuggi-Jhompri (JJ) clusters – temporary settlements housing thousands of low-income families. Housewives, they found, were the most vulnerable as they were responsible for water storage and cleanliness.

In 2015, a peer-reviewed analysis found that poor access to water, sanitation, and hygiene played an understated role in determining maternal and foetal outcomes. “Whilst major gaps exist, the evidence strongly suggests that poor WASH [water, sanitation, and hygiene] influences maternal and reproductive health outcomes to the extent that it should be considered in global and national strategies,” the paper noted.

On ground, a blind spot thus takes hold – among the health practitioners, community health workers, patients, and their families. Pregnant people are never one told the water they’re drinking, or anything else they may be doing, could pose a threat to their health. The person, then, is not quite thinking about their health while engaging with these tasks. And if a disease is not going to affect them any differently, why would they visit a health centre at the trigger of a relatively familiar symptom?

On the occasion they do, dengue-specific symptoms “are often dismissed as part and parcel of pregnancy – even when they shouldn’t be,” Dr. Gupta notes. Complaints of fever and vomiting are dismissed with the insistence that some amount of nausea is within the realm of normalcy in pregnancy. It is only when the clinical symptoms stretch into the zone of criticality – when people become weak or lethargic or present with other symptoms — that is when the illness becomes a “problem” to be managed.

Historically within medicine, a woman’s pain is never quite approached with legitimacy. A wealth of literature speaks of how women’s health issues invite only scorn and little interest. Dengue is no different “Complaints about fatigue, with or without a tropical disease, are met with violence within the household. A woman wouldn’t even complain about how tired she is feeling, because she fears violence from her partner,” points out Anugraha Raman, an associate at Belongg, a social venture that looks at intersectional inclusion in healthcare. Indian women suffer “extensive gender discrimination in healthcare access,” and gender stereotypes like those of normalising pain during pregnancy only work to prevent women from voicing their discomfort.

When pain and illness are recognised, it is spoken of in very specific ways. “There is no real individual focus on the pregnant mother, it is always very closely tied to the foetus’ health,” Raman adds. The body is a vessel, breeding life, and this life must be protected. This lens has persisted across different health parameters, wherein pregnant women are rarely studied as individuals. When they are, it is to measure and map the outcome of foetal health.

Consider the limited data we have around dengue and pregnancy: much of it still focuses on foetal complications and is oriented at safeguarding foetal outcomes. Or the way prevention and control policies are framed around vector-borne diseases. Before dengue, there was Zika. During the spread of the Zika virus in Brazil, one of the preventive measures involved spraying a globally-approved pesticide called pyriproxyfen to curb the high cases. Women are disproportionately exposed to and affected by pesticides in both occupational and non-occupational settings, and it is this exposure that has been linked to acute and chronic diseases over the years. That pesticides pose a threat to women is not novel knowledge. But, it took a network of whispers and scientific data proving that pyriproxyfen was harming newly born children for Brazil to reconsider this prevention control.

Even the metric of maternal mortality ratio – which India claims has significantly improved over the years due to persistent support – is quite deceptive and limiting in its claims. India’s investment in maternal healthcare infrastructure far overshadows the resources allocated for bettering sexual and reproductive health services for its women. “Until we prioritise women’s health, until we stop asking women to prioritise the foetus’ health, this knowledge gap will always be a problem,” Raman adds.

“We should ask questions about how the pregnant woman is doing, for simply centring the woman’s health is sort of the best way to treat dengue from a gender-sensitive lens.”

Climate change and dengue

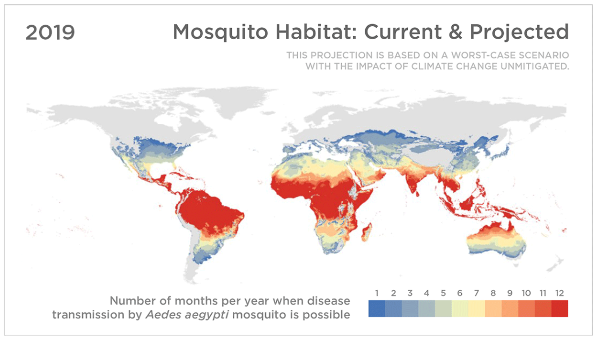

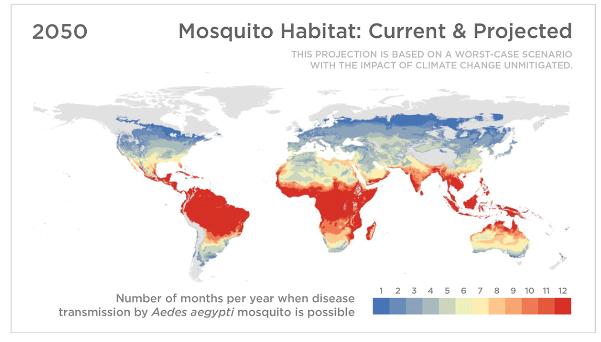

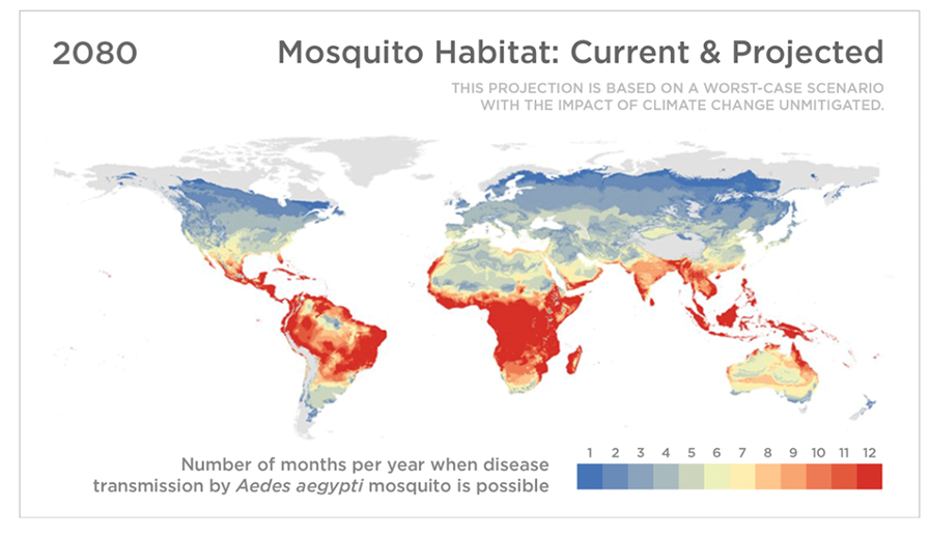

Practitioners screen for dengue only in endemic areas or where there have been a documented rise in cases. If it is in an area with limited cases, dengue barely enters the imagination. This practice is unsustainable, given the way global warming is altering dengue transmission. Rainfall, humidity, and temperature command where dengue spreads and at what rate.

In India, for instance, the number of months where the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes spread the infection has risen to 5.6 months each year, according to The Lancet. Monsoon patterns are shifting, meaning nearly half of the year serve as suitable months for dengue vectors to thrive. Another study from 2019 finds that dengue is widespread in coastal areas, characterised by “population density, socio-economic, climatic and the physical environment,” which is also leading to a “rise in cases in early months of the year compared to previous years.” It is expected that dengue’s transmission months might extend up to 12 months in most of the states eventually. Dengue infection is becoming more frequent, casting a grim outlook over the health burden.

Source: Sadie J. Ryan, Colin J. Carlson, Erin A. Mordecai, and Leah R. Johnson. Credit: Koko Nakajima/NPR.

Urbanisation is acting as a catalyst too in ushering this fluctuation. Glass buildings and lofty developmental projects are gaining heft without paying heed to developing proper drainage systems. Deficient water management systems, including but not limited to water storage practices, allows for proliferation of mosquito breeding sites in urban, peri-urban, and rural areas.

When thinking about the climate crisis in the context of global health, women are found to be disproportionately affected. Early data shows pregnant women from India’s Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Adivasi communities are more likely to have adverse maternal outcomes due to restricted access to affordable healthcare. These communities are also more likely to be exposed to the mosquito carrying the dengue virus – as they live in temporary settlements across peri-urban and rural areas that are notorious for malfunctioning systems that allow for water-logging and the spread of water-borne diseases.

Gender and caste both are able to explain how class differences operate when it comes to healthcare access, and arguably, Raman points out, “caste lens is a more useful lens, it impacts vaccine uptake and engagement with the healthcare system.”

Cure for a neglected tropical disease meets gender barriers

The lacking awareness, at one level, reflects the neglected status of dengue. The actual number of dengue cases were 282 times the number reported by the national vector-borne disease control programme, according to one study. If at one point in global health conversation dengue was a sleeping giant, it’s waking to exact a heavy toll.

One pillar of dengue management is early diagnosis. “A successful clinical outcome requires efficient and early diagnosis of cases provided by accurate differential diagnosis, rapid laboratory assessment/confirmation, and early response to severe disease,” the WHO noted in its recommendations. Diagnostics is one piece in this larger puzzle of building resilience against a neglected tropical disease. But insufficient stock piles, inaccurate results, and limited distribution of testing kits has so far meant much is left to be done in this sphere too. Moreover, research lags behind in identifying the biomarkers that can help predict disease severity.

“These outbreaks keep on happening, and so many diseases go undiagnosed,” Dr. Gupta laments. “And in India, we don’t even know what the patient died of.” Dr. Gupta argues that allocating budget towards dengue testing will build up the necessary awareness and will. Strengthening dengue testing holds some answers, as it allows for early detection and negates the scope of misdiagnosis.

Screening and surveillance carve out path for accessible treatment. But currently, there is no decisive, specific antiviral drug to treat dengue, which makes dengue vaccine a promising pillar. Dengue vaccine needs to be four-time more efficient than a standard vaccine, like one for Covid-19. Unlike Covid-19 that is conventionally caused by a single strain of Sars-COV-2, dengue fever is caused by any of the four related viruses — DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. Let’s say if the vaccine provides protection against one serotype, one would still be susceptible to being infected from other ones.

But “the main challenge to do research in this area (and all areas related to dengue), is the lack of funding,” Dr. Malvike adds. “The fact is that very little funding is available for dengue, and to answer these very important questions [of gendered treatments].” Dr. Malvike raises existential question around the process of drug discovery and development. Big Pharma has a role to play in deciding what diseases are deemed worthy of a cure, and which aren’t, and much of it has to do with profitability. There is a need for funding into research strategies for not only new medicines, but for vaccines for dengue and diagnostics that are accessible to people who need them the most.

There are players in the mix though: Sanofi Pasteur’s Dengvaxia – the world’s only licensed dengue vaccine – is currently in clinical trials in the country. Panacea Biotec Limited has completed Phase-1 and Phase-2 trials. As of September in 2022, the Indian Immunologicals Limited (IIL) had begun conducting Phase-1 trial of dengue vaccine (it would take as long as five years to conclusively glean anything from trial results). Takeda (TAK-003) recently registered its dengue vaccine in Indonesia, and is observing long-term data, with the promise of developing a vaccine that has the potential of providing protection from all serotypes.

Despite tepid developments, policymakers, practitioners, and people have looked at dengue immunisation with scepticism. What if the vaccine is not safe, and causes more harm than it seeks to solve? That was the case with Dengvaxia, when in 2017, the vaccination led to hospitalisation and death among children in the Philippines. Dengvaxia worked only if someone had a dengue infection in the past, which eventually led to the decline in its use, “because it’s difficult to test individuals before vaccination if they have had dengue in the past,” Dr. Malvike explains. Dengvaxia’s trajectory was a cautionary story in mapping out what not to do while thinking of immunisation.

Ambiguity doesn’t do well for vaccine uptake, and the immunisation among pregnant women has suffered from misinformation and a lack of trust in the healthcare system. Interestingly, despite being important target groups for vaccination, the current clinical development has not included pregnant women as an experimental group – a fact in line with how vaccines are discovered and developed for every illness.

During pregnancy, any form of injection or medical intervention is met with reluctance. What if the injection leads to miscarriage, or causes abortion? “It could happen again,” Dr. Gupta fears, “that when a dengue vaccine is launched, there might be reluctance because pregnancy itself is surrounded by myths.”

Developing a dengue vaccine is a war half won – there will be a major need for acceptance among pregnant women, who present a high-risk group. “If dengue vaccines do indeed enter the picture, and if vaccine awareness is to be spread, we should start running campaigns at a state level from now,” notes Radha, who has supervised multiple awareness campaigns in her area. Awareness around dengue would also prove effective for other infections spreading through the same vector, like Zika virus, which is spreading silently and swiftly through India.

Radha hints at being more proactive – the only strategy befitting for a disease that is creating massive blind spots in health care.

Transmission of knowledge

There is no affordable, singular drug. There is no vaccine, at least in the future. Vector control programmes and environmental management plans are helpful, but spraying insecticides or fogging remain futile if not combined with building resilient infrastructure that eliminates the accumulation of dirty water in the first place. It is akin to throwing darts in the dark.

Is there a bull’s eye?

If the tiny black circle could speak, it would point to the need for raising awareness to close the knowledge gap. Public health policy is not always measured in terms of longevity or sustainability, but how well it is able to address a crisis of the present. And the current lacuna bears signs of ignorance.

Among patients and families, awareness involves being vigilant about symptoms. For instance, if someone has a high grade fever of more than 104 degrees that occurs in a cyclical pattern, one accompanied by shivers, then it could point towards an infection like dengue. Other symptoms like nausea, severe muscle pain, or severe headaches – similar to Tara’s case – should also inspire caution on the part of the family.

A more potent message can come through health service providers themselves. Here, the role of health practitioners and community health workers (CHWs), like Anganwadis and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), becomes paramount. In peri-urban and rural settings, CHWs, like Anganwadis and ASHAs, are vanguards of women and children’s health. ASHAs, for instance, counsel pregnant women about antenatal care, advise them on danger signs during pregnancy, help them prepare for birth, even take them to the local hospital for delivery. The information they hold and the status they command can be potent vehicles for knowledge building around dengue.

ASHAs routinely talk to families, the village elders, gram panchayat about women’s health issues. “If they replicate the same pattern that exists for other health interventions,” Radha reckons, “and if they are able to communicate the real-time evidence, acceptance will increase about treatment and care.” Advisories – such as those suggesting pregnant women to use insecticidal body spray or room spray – may encourage caution when coming from a community the women know and trust.

If at the grassroots level the CHWs are able to vouch for the vaccine, then uptake is higher. But the lack of awareness can bolster gendered biases, creating a scenario where CHWs become carriers of fear and misinformation. “CHWs also may hold any stereotypes about how important the foetus is, or monger fear. They might withhold information about the vaccine, which they think may affect the foetus,” Raman notes.

Put differently, a pregnant woman who comes in contact with the health system should get vaccinated more easily. But whether or not she does, “depends on the kind of healthcare service provider she comes in contact with.”

Awareness can spread through conversation among village elders in local communities, ramping up dengue screening in other areas, training practitioners to identify dengue symptoms among pregnant women in particular – all are conducive to early detection and treatment.

Due to the scattered nature of cases in India so far, even the doctors across urban and peri-urban areas carry limited knowledge. “Those who haven’t experienced cases, if you talk to them, they won’t be able to tell the basic symptoms and differences about dengue diagnosis,” Radha notes. The knowledge gap may also mean the health providers never quite approach complaints of flu or nausea in pregnant women with the urgency the case may deserve. “[Dengue’s impact on pregnant women] is a really important area in maternal health, and we need to be really careful before dismissing important symptoms,” cautions Dr. Gupta.

Knowledge can carve a path towards early medical advice, strict monitoring, and symptomatic treatment. “Pregnant females with high risk predictors should be identified and managed aggressively in intensive care units to improve outcomes,” Dr. Ruchita’s paper concluded too.

The onus on skill building and training health service providers inevitably lies with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. India’s most updated manual on vector management by the national body on disease management makes no mention of the added risks among pregnant women, or the kind of focused care they may need.

The way dengue is growing and changing demands reworking our current guidelines, training, and education systems. It will decide how practitioners are trained, what they are taught, who is prioritised, and who is forgotten.

What makes women vulnerable to dengue fever is a question asked and answered in three ways: biologically what happens to the female body during pregnancy, scientifically as to how the climate crisis renders them more vulnerable, and socially how historically a maternal bias and their limited access to healthcare restricts treatment.

There’s a famous tale that speaks of six blind men trying to figure out what a huge elephant looks like. One man touched the tusk, others the legs, the belly, the tail, the ear, and the trunk. But none of them quite agreed on what the elephant could possibly look like, because they were looking at different things, but that didn’t mean the individual people weren’t right.

Addressing dengue is somewhat similar, with some noting that treating dengue is like a 100 men trying to solve a neglected disease. Different stakeholders may wrestle with different parts of dengue – diagnostics, treatment, immunisation, vector control – and each may tell a different story.

The only moral here becomes rather humbling: dengue requires more than 100 people – not just men – trying to figure out the anatomy of a disease.