[Part of] CHAPTER 1 – Will Eat Anything Once

I have a clear memory of my own from when I was around four years old, in our family kitchen. On the squeaky laminate floor, designed rather unconvincingly to look like tiles of slate, my mother had carefully spread sheets of newspaper lifted from the local Chinese grocer. She had then placed her heavy stone mortar over the columns of Chinese characters communicating the news of the day and ads for cheap flights to various destinations in Southeast Asia. She sat on the floor in the afternoon light, pounding chillies, eschalots and other heady aromatic ingredients to make a spicy sambal. The rhythmic thumping of the stone pestle on spiced paste vibrated through the floor; I could feel it with my feet. Dust glittered within the shafts of sunlight streaming through the kitchen window, illuminating the fiery red hue of the paste as its individual elements came together as one. This labour-intensive process was just one of many that would create a dish to grace our dinner table that night. That meal marked no special occasion, yet in my mind the memory feels weighty, bathed in deep significance.

Other childhood food memories were . . . stinkier. On days when piles of dried shiitake mushrooms were sorted and soaked in pots of hot water, the earthy, pungent, sulphurous aroma permeated every pore and repelled us children out of the house until dinnertime. The magnitude of those mushrooms would be tamed when they were integrated into rich soy-braised meats, gingery steamed fish, and verdant vegetables lacquered in a gloss of oyster sauce and sesame oil. The symphony of aromas from our culture was anchored and balanced by those forceful little fungi. Our deep desire to escape was futile, because by the time we could smell those damned mushrooms, the foetid fragrance had already embedded itself deep into the fibres of our clothes, skin and hair. This was an invisible mark to the kids in the neighbourhood with whom we played; the kids from whom we, as the only non-Anglo family in the street, were different in so many more ways than simply appearance.

It strikes me now that those memories form a crucial part of the bedrock of not only my career, but also my life as a whole.

Food wasn’t just sustenance, but a language we learned from birth – a way of communicating deep love and affection in a culture that often finds it difficult to do so by way of a hug or even an ‘I love you’.

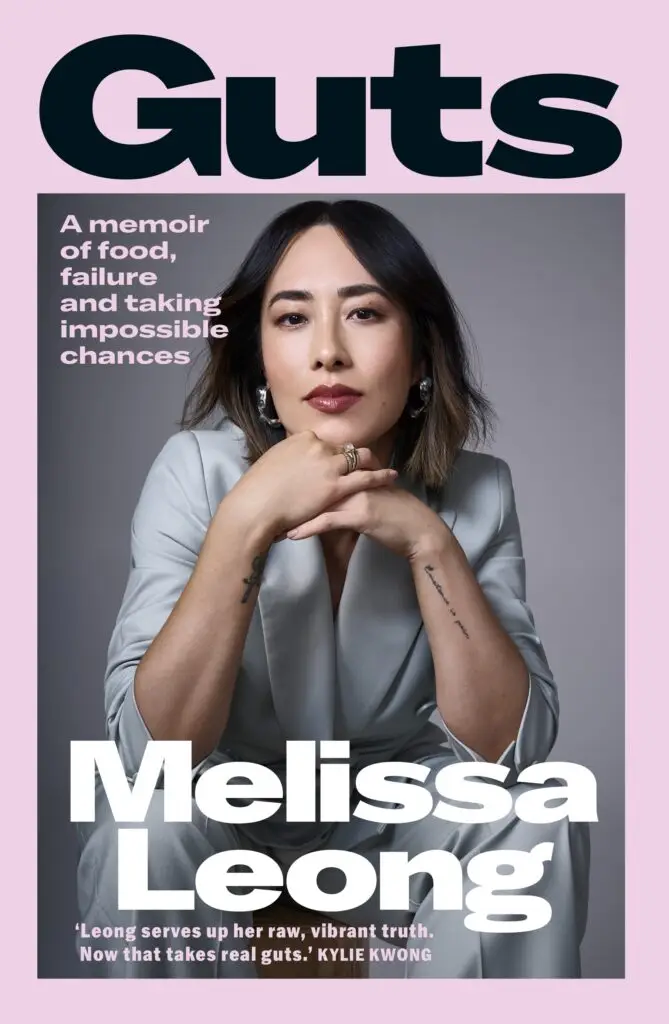

Melissa Leong

To my knowledge, all Asian children are only allocated two ‘I’m proud of you’ statements a year, but don’t quote me on that. Similarly, issues of mental health are never discussed. My bouts of feeling low or anxious as a child were chalked up to ‘being moody’, and as a small human, I lacked the language to articulate further if anyone had thought to ask. In my experience, many emotional things a Chinese parent wants to say, but can’t, are said with food. In my family, as with many, food was a reward. More than mere sustenance, it was a luxury, an incentive, a way of smoothing over a bad day. Most crucially, of saying ‘I’m sorry’, and that most elusive of all sentiments, ‘I love you’. At my house, there were pots of pork bones braising with carrots, onion, ginger and garlic in broth until the meat barely clung on. The bones were fished out of each pot and drizzled with soy, a homestyle favourite thing to do at ours. Extra points if you got a piece with the marrow intact so you could push it out with a chopstick or a finger and slurp it up, its fatty plushness coating your lips with clinging richness.

Whether home-cooked or eaten in one of many crowded restaurants filled with the squeals of children, the low hum of chatter in multiple Asian languages and dialects, and the tinkle of melamine chopsticks on porcelain bowls, food was the great escape from reality and the work to be done. No matter what the day brought, the woes of the world would stop in a mouthful of noodles rising like a charmed snake from a bowl of soup, the steam creating a fog of humidity around your face as you inhaled ginger, garlic, shallot, pork broth. Just one slurp made the world a better place.

Every Sunday for as long as I can remember, our family went to yum cha. We’d clutch the ticket and wait patiently for our number to be called, our necks craning to see which lady had which trolley, useful information for later. I have such a strong sensory memory of these meals. The clattering of teacups and bowls on tabletops; the sound of voices shouting in Cantonese, Mandarin and accented English. The smell and feel of starchy linen tablecloths about to be Jackson Pollocked with soy, chilli and the juicy bits of dishes hastily thrown on the table by surly staff. The scent of savoury steam as carts whizzed by, housing all manner of delectable delights that could, if you asked nicely, be yours.

My favourite dishes have more or less remained the same since then. Har gao, those crystal-wrapped translucent skins, plump with prawns and just a tickle of ginger. Siu mai or – as I like to call them – ‘gwai lo’s first dumpling’, these opentopped, wonton-wrapped wonders look enough like dim sims that a non-Asian might dispense with fear and give them a go. Cheung fun, long, slippery steamed rice noodles filled with sweet, sticky barbecue pork or ginger-spiked prawn, to be dipped in an alchemic concoction of sweet and salty sauce. On our table, we’d also have lo mai gai (sticky rice parcels – the best ones have a little cube of salted duck yolk in the middle) and lo bak gou (squares of pan-fried daikon cake studded with tiny dried shrimp and Chinese sausage). I also love wu gok, with their fine deep-fried, lacey aura encasing a deeply savoury taro and pork filling. There’s something about yum cha that always feels like a special occasion to me. Each steamer basket and plate is a gift to unwrap and enjoy. Sitting around the lazy Susan (poor Susan, she ain’t lazy, she works hard!), time stood still, and gluttony was encouraged.

To this day when I’m feeling low, I seek out these treasures to buck up my spirits and heal what ails me. When I was a kid, it wasn’t all that existential. Sunday’s yum cha leftovers became an easy Monday lunchbox filler, and all morning I would think about which ones Mum had packed and what dumpling I’d eat first (I would always save my favourite till last). It was a battle of waiting until morning tea or lunch to eat them, but that battle also contained the dread that would come with my classmates playing my least favourite game: ‘What’s That Smell?’

I’ve come to realise that when kids do this, it’s usually coming from a place of uninitiated curiosity and not of pure disgust or hatred. Usually. Those unfamiliar fragrances were of my heritage and not theirs, though happily that’s changed a lot over the years as Australians have grown in their obsession with food of all cultures. I smiled recently when I read a school lunch menu stuck to the fridge door at a friend’s house – there was sushi on that menu! What?!

In cartoons, good smells are often depicted by a disembodied arm beckoning the characters closer. I can still smell that mixture of Tupperware plastic slowly baking in a backpack throughout the day and the waft of whatever was inside it the moment I popped the lid. In the playground, the cartoon finger of my lunchbox’s aroma lured my classmates over to peer into the trove of wonders packed by Mum, and I took great pleasure in explaining what I was eating. Sometimes I’d even let them try a bite if they wanted. (I am, by my own admission, a feeder.

From a young age, I had already figured this out about myself.) Sometimes, though, kids say hurtful things about what they don’t understand. My lunchbox was a daily source of happiness that did not contain Devon sandwiches, storebought biscuits, or parched sticks of carrot and celery with nothing to dip them into. (Devon, for those who haven’t had the pleasure, is a sliced lunchmeat of indeterminate origin.

In my career, I’ve become pretty good at being able to guess what goes into most things, but on this particular subject I remain mystified.) So sometimes that happiness came served with a side of unconscious racism, hold the tomato sauce.

Inevitably there’d be a kid whose fear outweighed their curiosity, and instead of questions, I witnessed pinched fingers over noses or, worse yet, index fingers pulling up the outer corners of eyes in mockery of me.

Melissa Leong

My parents had chosen to settle in the heartland of Sydney’s Sutherland Shire, colloquially known as The Shire, home of Sylvania Waters, The Sharks and the Cronulla riots. Can’t say they weren’t committed to the full Aussie experience. But being Chinese at a primary school that only had one or two other Chinese families present meant we were conspicuous. It meant that we few carried every stereotype possessed by the Asian diaspora, like we were a single nation. Chinese burns were an acceptable way for kids to hurt each other in the playground, and teachers would pretend not to hear ‘Ching Chong Chinaman’ being whispered when I’d walk past.

That stuff stays with you long after you’ve left the playground. I remember a kid walking up to me, pressing a finger to my chest and calling me a Gook. Talk about pointblank racism, shots fired. I was so shocked, I think I walked away without saying anything. In a predominantly AngloSaxon school, the unspoken code was that ethnic kids would stick up for each other. I felt heartbroken that this Greek kid didn’t see fit to include me under that coloured umbrella of protection. It was then I realised that even among ethnic groups there was a hierarchy, and I wasn’t at the top of it. We were Gooks, Chinks, Chinamen and Ching-Chongs – and, apparently, dirty. I don’t think this last insult had to do with the fact that we are a shower-twice-a-day, wash-your-feet-before-getting-into-bed culture. Being excellent at maths and music didn’t help me prove them otherwise.

To this day I think that if you’re going to be racist, I suggest you at least be specific or accurate about it. Having had weird school lunches is a badge of honour I now share with so many others as adults. For some of you other weird lunchbox kids, it might have been dolmades, slices of cold cotoletta between focaccia, leftover curry and rice . . . We each have our particular trauma about it, so we’re bonded, okay? In an environment so culturally different to home, those lunchboxes held artifacts of identity, a reminder of who we are and where we come from. But back then, the antidote to my Asianness was something I took seriously.

For the longest time I just wanted to fit in, as all kids do. I did Nippers, got my Royal Life Saving Bronze Medallion, chose surfing or beach sports as my PE electives at school, wore Kuta Lines and worshipped Elle Macpherson. I also coveted the idea of having blonde hair, a plunge I will probably never take but will always wistfully dream of. After a bout of slanty-eye pulling at school, I’d usually ask Mum for a ‘normal lunch’ (which is to say, sigh, Anglo-style). Bless her, she had to ask me what those blond kids had in their lunchboxes. When I told her, she looked utterly horrified. There would be no Devon and tomato sauce on Wonder White for me because we were not . . . wonder white. Ever the A-type Asian, Mum took the brief of ‘please give us white bread with stuff inside’ to the nth degree. She’d buy flourdusted bap rolls and fill them with seeded mustard, glossy pink ribbons of double-smoked ham and generous wedges of squishy Camembert, and she always separated the tomatoes so that the bread wouldn’t go soggy.

The word ‘flour’, incidentally, is pronounced by Singaporeans in a very specific way. If you’re posh or European you might pronounce it as a delicate ‘flao-ah’, blending the syllables together softly in the voice of the actress Emily Blunt. If you’re Australian, it’s very decidedly ‘flao-WAH’, in the style of Kath and Kim. If you are Singaporean, it’s a single syllable, ‘flah’, in the style of . . . my mum. When asked what that white stuff was on the top of my roll, I’d be teased mercilessly for telling them. It was only then that I twigged how different my parents sounded to everyone else. Another favourite Mum-lunch I loved was a sandwich of roast chicken (a healthy ratio of skin and stuffing to meat), layered with avocado and a mayonnaise made with freshly picked tarragon from our garden. Even when she was trying to be ‘normal’ you could never, ever accuse my mum of being basic. Honestly, I haven’t the faintest idea where I get it from.

Top photo – Pictured: Melissa Leong, Source: Supplied

Other articles you may like: