I was having flashes of pain in the bottom of my left breast. I examined both breasts and while I felt no lumps, the bottom of my left breast was sore to touch. I gave it a few weeks. The pangs were still often and sharp enough that I booked in to see my GP, ‘just in case’.

Appointment One

My GP performed an exam and the same spot hurt, but she also felt no lumps. I had no family history of breast cancer. She hypothesised it could be a pulled muscle. I’d recently had my first reformer pilates class in months – of course it was a pulled muscle! I was instantly relieved, soaking in this diagnosis. She offered a referral for an ultrasound, “just to rule anything else out”. I’m a better-safe-than-sorry type of girl, so I said yes please.

Appointment Two

In the waiting room ahead of my ultrasound, Edwina Bartholomew was on Sunrise announcing on live television she had cancer. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. It hurt when the technician pressed the ultrasound wand on that same spot. The machine hummed and clicked inscrutably. When the technician left the room to get the radiologist, I took a selfie on the ultrasound table in the disposable gown with a handt owel over my bare breasts, sticky from the gel. I imagined it would be a funny keepsake one day – remember the time I got an ultrasound on my tits and it turned out to be nothing??

The radiologist came in and said they found something. She was 99% sure it was a fibroadenoma, a non-cancerous tumour. The words ‘non-cancerous’ and ‘tumour’ vied for my emotions. Should I feel fear? Relief? Abject shock? She pointed it out to me on the screen. It looked big and dark and menacing – at only 18 x 9 x 15mm. Something so tiny was holding my left breast hostage, too deep for me to feel. I burst into tears. The radiologist comforted me: “If it’s anything worse than a fibroadenoma, I will fall out of my chair.” It didn’t comfort me. People fall out of their chairs. Doctors are wrong. Women are medically gaslit. Every day.

She said a fibroadenoma is like a mole. You can live with it for years – as long as it’s harmless you don’t have it removed. But you do have to monitor it for growth or changes, in case it becomes no longer harmless. I was referred for a biopsy a few days later to confirm. I sobbed in the car, telling my boyfriend and best friends the news via messenger, because I knew I couldn’t handle telling them in person. I pulled myself together for the Maccas Drive Thru.

Appointment Three

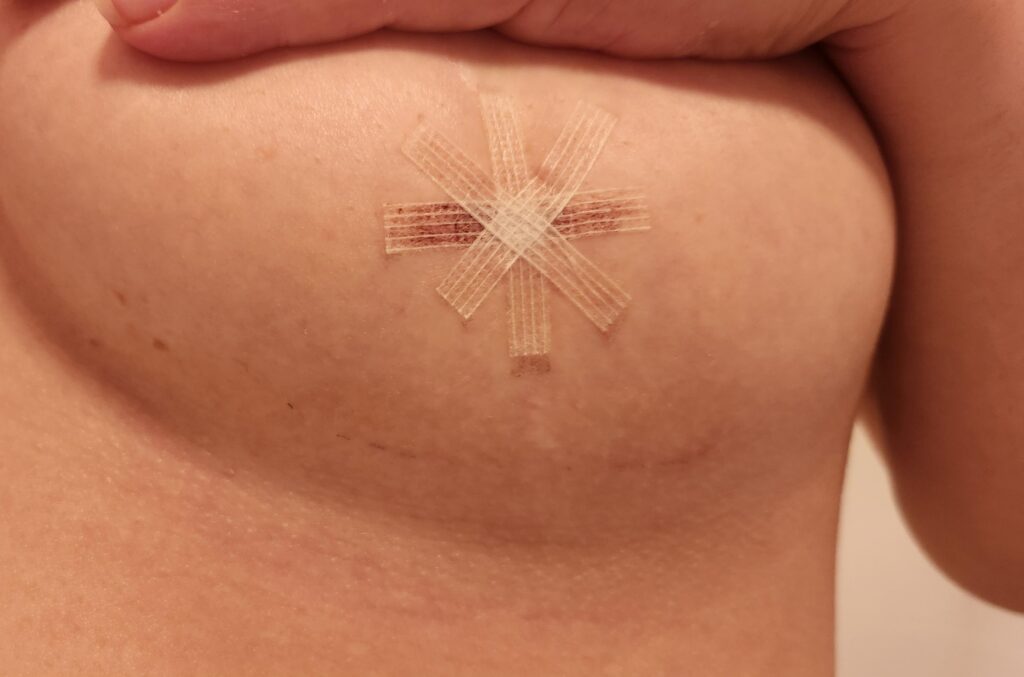

In the ‘ultrasound-guided core biopsy’, one woman held the ultrasound wand on my breast so the doctor knew exactly where to go. The doctor injected local anaesthetic, made a small incision, and took samples. There was a loud clicking noise for every sample she took, and my whole body flinched as a reflex. Thankfully the doctor had demonstrated the clicking and told me what to expect before she started, so it wasn’t a shock. I couldn’t feel pain, but I could feel it happening. A third woman was in the room just to support me, her hand on my leg, telling me how well I was doing. I appreciated this stranger’s tenderness more than I could articulate in the moment. She said goodbye and good luck.

As soon as I was bandaged and sitting up, distant pain awakened, vibrating from my breast, dulled by a mini ice-pack placed inside my bra. I gingerly drove myself home. Naturally, I’d been thinking about mortality a lot in the days since I learned what a ‘fibroadenoma’ was, thinking about the life I’m yet to live, the children I’m yet to have. I was watching a documentary about babies, when my sister rung and told me she was pregnant. I hadn’t told my family about any of this yet, as they would worry, and I couldn’t worry about them worrying. My breast throbbed, freezing and numb.

Appointment Four

The results confirmed it was non-cancerous, and I would need a follow-up ultrasound in six months. My GP gave me the news in a telehealth appointment that was 30 minutes behind schedule. Every second I waited felt like a minute. Every minute stretched like an ocean.

The six days between the ultrasound and receiving the biopsy results were interminable. What was inside my breast was the last thing I wanted to think about, but the only thing I could think about. From thinking it was a pulled muscle to learning it was a tumour that was most likely, currently, non-cancerous, I was emotionally and mentally drained. I was relieved, traumatised, grateful, weary, fortunate, exhausted, on a loop.

I only reached my diagnosis because I advocated for myself again and again, and chose the time-consuming and expensive path. The initial GP appointment, the ultrasound, the biopsy procedure, the telehealth appointment to receive my biopsy results (all of which were during work hours, of course), and THEN the surprise bill in the post for the pathology of the biopsy, cost me $1,249.15 out of pocket – and I only got $572.85 back from Medicare. Thankfully I had the money and the time. Thankfully I made the time.

I learned along the way, fibroadenomas are surprisingly common. My friend also had one diagnosed in 2024; another friend’s mother has had one; and the first ultrasound technician told me she’d had multiple throughout her life that were all harmless. Some of these were discovered because of a noticeable lump – mine was discovered because my body was shouting at me something was wrong.

Early detection is crucial. As well as my breast, I also have to monitor my cervix. The surgery I had in 2020 was to remove abnormal cells detected during a cervical screening, that if left unchecked can become cervical cancer – so going forward I need more regular than average screenings. My next cervical screening is due in February, and my next breast ultrasound is due in March – welcome to 30 years old! Such is the relentless medical invasiveness of being a woman.

My biopsy scar has faded. Living every day with a tumour inside my breast, and overanalysing every twinge is my new normal. The chance it could turn into something worse is unbearable. The chance it might not is a privilege.

Being proactive about my health is a gift I will never take for granted, and urging other women to listen to their instincts, trust their gut, feel their breasts, and advocate for themselves may just be one of the most important things I ever do.

Eleanor Danenberg loves to explore feminism and pop culture in her writing, and has been published by ABC, The Guardian, Fashion Journal, and more. Eleanor, who is Macanese and mixed-race, was raised in Mildura and lives in Adelaide. She posts about books, cooking, fashion, and all things secondhand on her Instagram: @eleanorwrites_